Going Whole (or Half) Hog: Buying Pork Direct from the Farmer

When meeting Wolfgang Ortloff at his home, it is not out of the ordinary to see a 200-pound Berkshire hog trotting by. Or to see a spotted snout poking out from behind an oak tree, followed by a resounding snort. Ortloff and his wife, Susan, raise close to 100 Berkshire and Duroc pigs a year on their 12-acre Worden Hill Farm in Dundee.

The pastured pigs reach a robust market weight slowly and naturally as they feast on locally milled grains and scraps from nearby gourmet restaurants and boutique food producers. Briar Rose Creamery, just up the road, brings buckets of whey left over from making goat’s milk cheese. In late summer, the hogs snack on fresh peaches from neighboring Baird Family Orchards, plus apples and hazelnuts in the fall. Artisan brewery Heater Allen provides an occasional amuse-bouche — buckets of spent grain. “After they eat it, they just lay there, smacking their lips with satisfaction,” says Susan.

The Ortloffs sell half and whole hogs to a handful of restaurants — Ned Ludd and Ciao Vito in Portland, and Thistle, Jory and Community Plate in the wine country. But most of their customers are avid home cooks who want to know the provenance of their pork and aren’t afraid to invest in a whole or half hog.”People are really excited about knowing where their pigs come from,” says Susan. “The health and humanity, the way the pigs were raised, are two main reasons.” The taste and quality of the pork is another, she adds. Berkshire pork is considered the “Kobe beef” of the pork world. When pasture-raised, the breed produces tender, dark, juicy meat with high marbling and intense flavors.

And for nose-to-tail devotees and adventurous cooks, purchasing a whole or half hog gives them the opportunity to have access to all parts of the animal because they have a direct dialogue with the farmer and butcher. That means they can take home all the unusual bits — skin, fat, trotters and head — to make recipes such as scrapple, cracklings, blood sausage and other charcuterie. Although this is something of a novel idea these days, it’s nothing new to Ortloff, who grew up in a small village in Germany. Once a year his family would buy a pig and invite the local butcher to the house for schlachtfest, a traditional German pig slaughter, followed by a festive meal with wine.

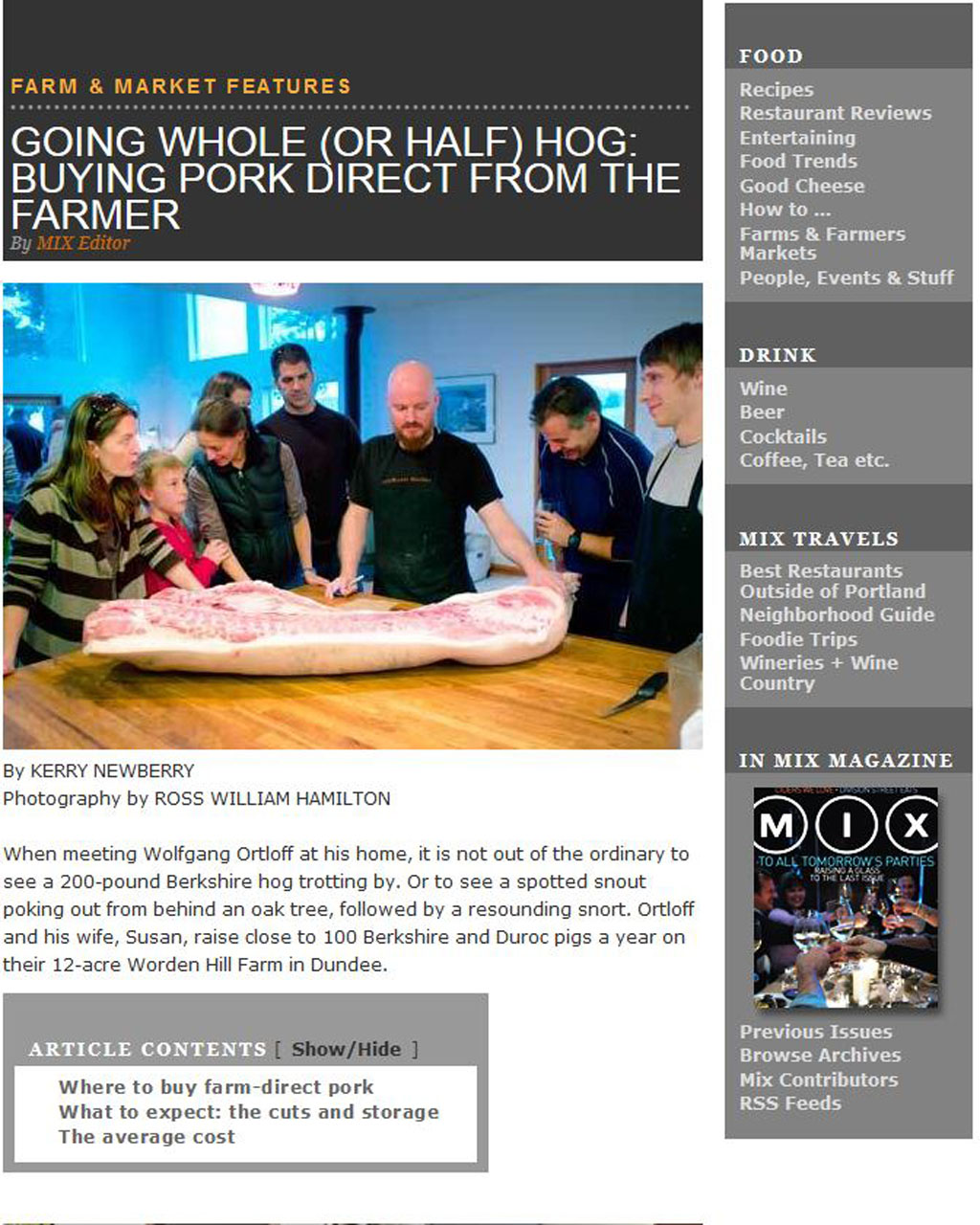

And that’s why, one sunny Saturday, the Ortloffs hosted a butchery affair for their customers, Bavarian-style. Imagine an intimate wine and cheese party, but with two butchers breaking down half hogs on the main table in the Ortloffs’ open kitchen.

“We raise the pigs, but this is where the true craft comes in,” says Ortloff, nodding toward the two butchers.

As 30 urbanites clad in Hunter Boots and dark denim sip wine and nibble cheese, and three young spectators sit perched atop stools, elbows on the wooden table, Spencer Adams and Devin Nowlin from Laurelhurst Market break down the first half hog of the day. While one butcher deftly glides a long, thin, flexible knife around the bone of a ham, the other uses a hacksaw to remove the trotters.

The meat belongs to Michele Meyer, the Ortloffs’ family friend from Seattle. This is her fourth time buying a half hog — her family loves pork and so do many of her friends. So much so, her Facebook post looking for people to share the meat quickly generated more responses than she needed. Splitting a hog with friends is a common tactic for buyers concerned about storage space and eating all the pork. A family of three or four usually cooks through a half-hog in six months or less.

“The bacon always goes first,” says Meyer.

Adams, a soft-spoken butcher with a red goatee, begins peeling back a thick layer of skin — the process is smooth, clean and methodical. Meyer took the skin last time, but she wasn’t sure how to use it. Adams chimes in that the skin can be made into cracklings or croutons — a trifecta of salt, fat and crunch that’s delicious as a topping for salads and soups, or as a stand-alone appetizer or side dish. Fat trimmings can also be rubbed in a pan and used as “pork butter” or rendered into lard.

“Do you want your feet and your hocks?”

Adams asks. Meyer muses, until Adams reveals that the feet are a secret ingredient in great soup or stock. If you simmer the trotters long and low, the natural gelatin releases. “This gives the soup a nice velvety texture,” says the butcher. “The hocks, just above the feet, are really good for seasoning any kind of beans,” he adds, and can be slow-cooked or cured and smoked.

“It’s fascinating to find out all you can do,” says Meyer, marveling at the ham hocks and feet being neatly wrapped in brown butcher paper.

Clark Brinkley, a nose-to-tail enthusiast, agrees. “You can go to the store and say, ‘I want some pork chops or a ham,’ but this way you get it all,” he says. “And you get to try all kinds of cuts that you wouldn’t have tried before, like schweinshaxe,” he says with a sigh, a delicacy he recalls fondly from a year spent in Austria. The German dish of spit-roasted pork knuckles (or uncured ham hocks) is cooked slowly until the skin is crisp and the meat is tender.

“The mystery is how do you start with this big thing,” Brinkley nods toward the half-hog, “and create all those little things,” he says of the primal cuts being further broken down, his eye on a roast for dinner.

The Laurelhurst butchers work with customers to cut and package to their needs. “If they have four people in the family, that’s four chops per package because they are going to freeze it, so you want them to be able to pull it out and use it as is,” says Adams. “That’s what I love about being part of butchering right now,” he says about working directly with customers. “It’s all coming back around to what it used to be.”

The next half-pig on the table belongs to Ben Conte. His wife just returned from their daughter’s soccer game, where she was taking pork orders on the field. Conte declares the roast sausages from their last Worden Hill hog the best he’s ever had (the sausage was custom-made at Laurelhurst Market).

The family split their first half-hog with friend Steve Baczko, who quips that the tail is the best part. (The tail can be braised, stewed or deep-fried.) This time they plan to give some of the pork to neighbors and in-laws, and have aspirations to pursue the craft of charcuterie. Home-cured coppa (cured ham from the neck muscle) tops the list. “The key is to make sure you get the right salts,” says Conte. “This is the absolute bible of curing and salting,” he continues, holding up “Charcuterie: The Craft of Salting, Smoking, and Curing” by Michael Ruhlman. The gospel of charcuterie speaks to using all parts of the pig, which is also one way to honor the animal.

The butchers are on the last hog when a winemaking couple arrive with more bottles of pinot noir and two warm-from-the-oven apple pies. “Wolfgang drove by with his truck filled with apples this afternoon, and asked, ‘Do you want any of these before I feed the pigs?’ ” says Julia Staigers, from the neighboring Crumbled Rock Winery. Staigers wants to make headcheese (pig head meat suspended in a jellied stock). She’s betting the Ortloffs will barter — one pig’s head for a bottle of wine and home-baked apple pie. It’s clear that nothing will go to waste today.

MIX Magazine | May/June 2012