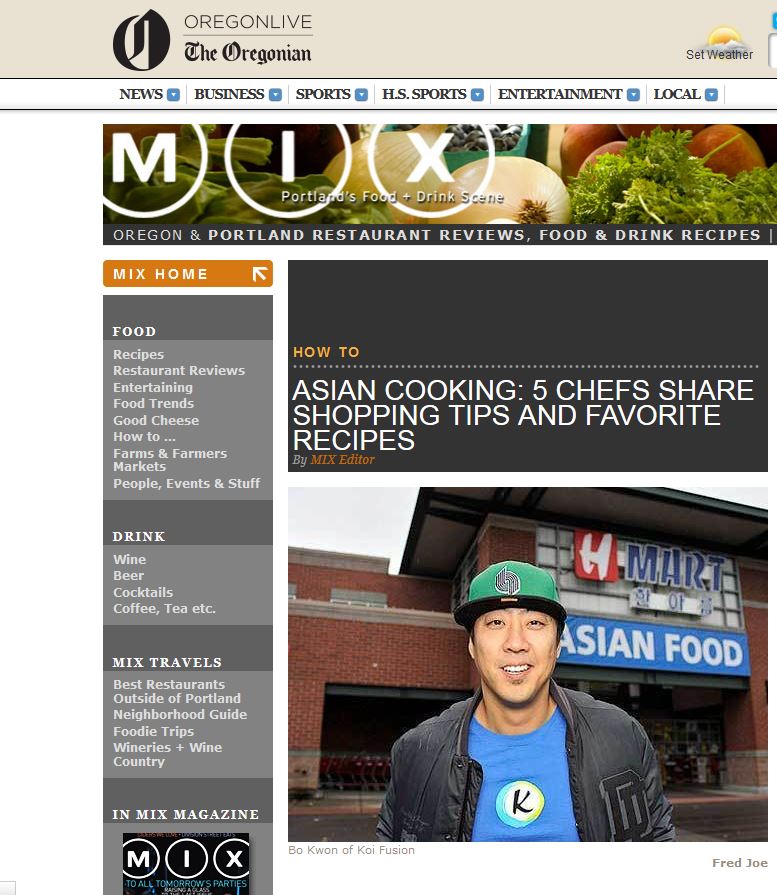

Asian Cooking: 5 Chefs Share Shopping Tips and Favorite Recipes | Chef Profile Jia You of Lucky Strike

Oregonian’s MIX Magazine, January 2013

The biggest hurdle to cooking delicious Asian dishes? Knowing — and finding — the right ingredients. How many times have you gone to an Asian market, recipe in hand and hopes high, only to leave dazed and confused? We know the feeling all too well. That’s why we asked five local chefs intimately familiar with the cuisines of Korea, Thailand, Japan, China and Vietnam to help us navigate our way through some of our favorite dishes. You’ll find their expert advice on stores and ingredients below, and links to their delicious recipes.

CHEF: Jia You of Lucky Strike

STORE: Oriental Food Value

RECIPES: Spicy and Sour Tofu Custard; Dan Dan Noodles

If you follow the gospel of Szechuan peppercorns, chances are you’ve dined at Lucky Strike. “We use it in about 80 percent of our dishes,” says Jia You, chef and co-owner of the restaurant. “This is the taste I crave most.”

The petite chef, as sweet as her food is spicy, has the peppercorns shipped fresh from China every few months. Technically not a peppercorn (it’s the dried berry husk of the prickly ash tree), the spice adds pungent lemony and floral aromas to many traditional dishes and gives your tongue a unique, tingly sensation that’s almost addictive.

You, a native of the Sichuan province of China, fell for Portland on her first visit to the city as a high school exchange student and later returned for college. “The only thing missing for me at the time was the food from Sichuan,” she says.

An accountant by trade, You and her husband opened the first rendition of Lucky Strike in a strip mall near Southeast 82nd Avenue and Powell Boulevard five years ago. The tiny, labor-of-love restaurant quickly gained a large and loyal clientele that followed the couple to their current location on the corner of Southeast Hawthorne Boulevard and 33rd Avenue.

The signature dish at the restaurant, dan dan noodles, is what You makes most often for family and friends. “Dan dan noodles are dear to my heart,” she says. After calligraphy or other extracurricular pursuits on weekends, “my parents always took me to get dan dan noodles.”

You recalls eating up to ten (tiny) bowls of noodles each time. “I specifically remember my mom asking, ‘Are you sure you want one more?’ And I’d respond ‘Yes, yes!’ ”

The name dan dan refers to the shoulder poles that walking street vendors would use to carry their goods; the two baskets swinging at either end held secret sauces in one, and noodles or tofu custard in the other.

The spicy and sour tofu custard is also one of You’s favorites. “It’s a very common dish in Sichuan,” she says. Some restaurants in the region serve only tofu custards; and in more remote areas, you can still find vendors walking through villages, tofu custard dangling from the dan dan on their shoulders.

You buys her tofu from Ota Tofu, a long-standing family-run company that uses all organic soybeans. When she is seeking Chinese-specific ingredients, she heads to Oriental Food Value in Southeast Portland, a family-run store that’s been in business for more than two decades. Not only does it stock her essential ingredients, but everyone knows her by name and the owners call her when her favorite ingredients arrive.

The first stop for You is often the aisle lined with dozens of bottles of Chinese black rice vinegar, an ingredient in dan dan noodles and the tofu custard. This vinegar can be a great mystery for the uninitiated. You makes it easy: Avoid vinegars that don’t have water listed as one of the first ingredients, and avoid those made in Hong Kong. Instead, look for bottles that feature the name of a town, because they follow the traditional Chinese process for making vinegar and will be fermented and aged.

One of her favorites is Chinkiang vinegar from the city of Zhenjiang in the Jiangsu Province (it has a bright yellow label). “This one is good for the sweet and sour tofu custard,” says You, “because it is not as potent as the more aged vinegars and it brings out a little sweetness so it is easier to balance.”

She recommends the Shanxi Superior Mature Vinegar for noodle dishes, like dan dan, because they can take a more intense flavor. The vinegar is aged for up to five years and hails from a region where vinegar has been made for centuries.

Oriental Food Value is also the only store in Oregon where You can find prickly ash oil, a Szechuan-peppercorn-infused oil that the chef drizzles over the hot and sour tofu custard, and it can be used to add pop to many Chinese dishes. “Once they run out they don’t usually get it in for another three to four months,” she says.