Sea-salt Kiss

“It was a bold man who first ate an oyster.” – Jonathan Swift

Perhaps Samus Heaney captures the allure of the oyster best in his poetry when he writes, “My tongue was a filling estuary/My palate hung with starlight/As I tasted the salted Pleiades/Orion dipped his foot into the water.” Ah, yes, that sea-salt kiss, fleeting bliss from the ocean. I don’t remember when I first fell for the oyster, but once I did, there was no turning back. Slurping from the half-shell, I always pictured oyster beds like a rampant berry patch, growing with wild abandon—each shell an effortless pluck from the sea, set on ice, with a squeeze of lemon, and a dash of mignonette.

Most of the oysters we eat are actually carefully cultivated, as wild oyster populations depleted due to overharvesting during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Pollution, habitat degradation, and non-native predators further challenged the bivalves to sustain themselves naturally.

Five species of oysters are commercially harvested in North America: the Eastern, the Pacific, the European Flat, the Kumamoto, and the Olympia, but there are hundreds of appellations. Rowan Jacobsen likens the oyster species to wine grapes in his book The Geography of Oysters. Though there are five varieties with classical characteristics, the flavor of each varies significantly depending on where they are grown.

When oyster aficionados think of the West Coast, Washington usually comes to mind: The state produces around 75 percent of all oysters grown on Western shores.

Oregon oysters are like Oregon wine, adapting the adage “small is beautiful.” The bays and inlets dotting the coast, from Netarts to Coos Bay, are tiny—and ideal for boutique production. The petit and pretty “Olys” is the only oyster native to the West Coast and often considered too small and slow growing for commercial harvesting. Luckily, Oregon’s tiny bays and inlets are ideal for small-scale growing of the Pacific and Kumamoto species.

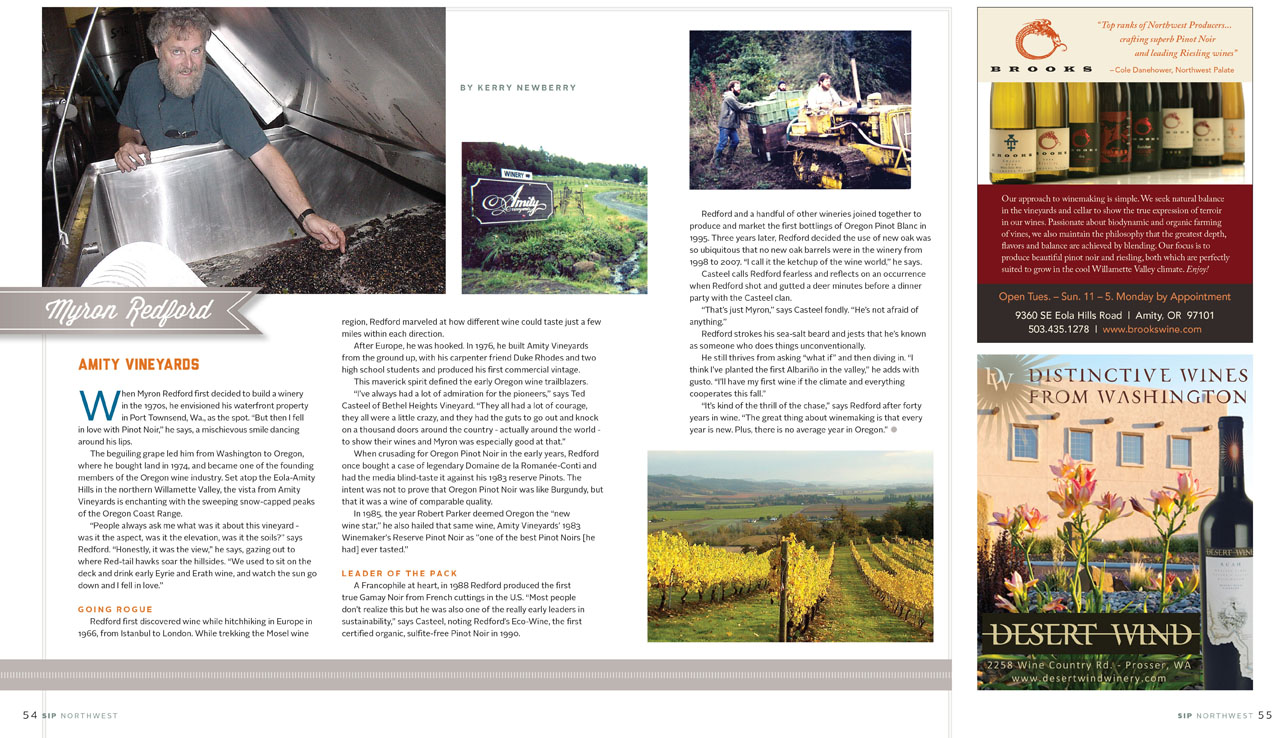

Xin Liu, a grower and co-owner at Oregon Oyster Farms in Newport, cultivates all three on Yaquina Bay. Established in 1907 by the Wachsmuth family, the waterfront business evokes timelessness as the rustic wooden floats sprinkle across a deep blue with the lavish green strokes of a forested backdrop. It’s like a Thomas Moran painting depicting the Wild West circa late 1800s. We stand in front of the only contrasting color, a castle of pearl white oyster shells, clearly a splash of abstract for the seascape.

“Aquaculture is just like farming,” Liu says, waving to the bay. “We have a hatchery, a nursery, and a place to grow the oysters. Followed by harvest.” Yaquina Bay is a deep-water estuary, ideal for suspension-culture cultivation, in which the oysters are suspended in water. Another technique places mollusks on the ground in large mesh bags or loosely scattered—a strategy more predominant in intertidal areas like Netarts Bay.

Xin LiuWhen cultivated in bags, the number of oysters is easier to track. You can count the bags at low tide, when they are visible. At Oregon Oyster Farms, Yaquina Bay is always under water. So Xin’s oyster garden—all 560 acres—is never fully visible. “We can’t really quantify what we have at one time,” says Liu. “Well, unless we dive around the bay counting,” he laughs.

Similar to wine, the taste of an oyster reflects its provenance, the place it comes from and how it is grown. “In every bay, the biological conditions are different, as are the physical—the wind and waves, the water temperature, the salinity, the pH. There are so many factors at play,” explains Liu. “Do you have more nitrates, more phosphates, or more trace metals?” All of these elements subtly shape the taste, appearance, and growth of an oyster. “Mother Nature is so dynamic,” Liu adds. The bay is always changing.

Liu reads the bay ecology like the academic he is. He left teaching at the Ocean University of China in 1992 to pursue doctorate studies at Oregon State University. He began his research at the Hatfield Marine Science Center in Newport, focusing on genetic diversity in oysters and water quality. His research subject was just down the river: Yaquina Bay. Around the time he was refining his dissertation, in 1997, a pearl of a proposition transpired to co-purchase Oregon Oyster Farms— and he accepted it.

“You can’t really learn from a textbook,” says the bespectacled Liu, as he explains his decision to leave academia for aquaculture. “You learn through field work and experience.” For a scientist partial to work in the outdoors, the intricacy of oystering fits.

Each week, the farm purchases around 20 million oyster larvae from the 30-year-old Whiskey Creek Hatchery in Netarts, the second-largest producer of commercial shellfish seed on the West Coast. Most growers rely on hatcheries because the West Coast waters are generally too cold for the Pacific and Kumamoto (both native to warmer waters in Japan) to spawn naturally. “In the early stages, the larvae free-swim in the water like plankton, the currents moving them back and forth,” explains Liu. This is a critical time: Oyster larvae are finicky, so if you do not have the perfect temperature, prime nutrients, and other nuanced growing conditions, the larvae will die.

For the past two years, every hatchery on the West Coast has been struggling to successfully cultivate oyster seed. Billions of oyster larvae have been decimated by a strain of bacteria, Vibrio tubiashii, that attacks larvae in their defenseless free- swimming stage. The bacteria appear to thrive in warmer waters, estuaries and bays, and the oxygen-starved dead zones that have infiltrated the West Coast over the past decade.

The effects will become more apparent in the next few years, after farmers have harvested current beds. Most oysters are harvested after two to five years of growing. Right now, the seed available to farmers is limited because the larvae are not surviving. Three years from now, there will be little to harvest because so few seed will have been planted.

Whiskey Creek is comprised of three buildings, each a maze of giant gurgling tanks pandering to larvae. Corners glow with rows of luminous green and golden jars, breeding a buffet of single-celled algae strains for nutrients. Under the watchful eye of hatchery staff, it usually takes about three weeks for the larvae to reach setting size, when they are ready to attach to a substrate (in this case, a shucked oyster shell provided by the growers). This process is called “clutching.” At this point, the larvae are transferred to the nursery tanks at Oregon Oyster Farms. Each temperature-controlled tank matches the 72 degrees at the hatchery and is filled with bushels of oyster shells. Upon release into the tanks, larvae clutch to the shells— their new homes—and begin to grow. These recently settled oysters are called “spat.”

When the spat, or baby oysters, are just visible to the naked eye, each settled shell is woven through yellow rope and suspended from wooden floats in the bay. Each 16-foot-long rope holds around 160 oysters. The 36- by 12-foot floats bristle with around 30,000 oysters at a time. Underwater, the scene might look like The Little Mermaid meets Rapunzel, flaxen braids dangling. Floats will move around, like crop rotation, as different locations in the bay affect the growth rate and shell development. After two years, the matured oysters get heavy enough that the tip of the float dips into the water—and that, says Liu, is the sign that it is time to harvest.

Ninety percent of the oysters Liu harvests end up on plates in Lincoln County restaurants like the Blackfish Café in Lincoln City and The Landmark in Yachats, and the remainder are air shipped to niche markets in Manhattan, Taiwan, and China, or are sold at Liu’s retail shop on his Yaquina Bay dock, where a two-man team deftly shucks 3,000 to 4,000 oysters a day, Monday through Friday.

“After we shuck the oysters, we take the empty shells and let them sit through the seasons,” Liu says. Winter rains give way to summer sun and the smaller pieces decompose, leading to second lives as compost for gardens. The larger ones will be used for substrate.

Though Liu lives and breathes by the mollusk, he never tires of eating—or talking about—oysters. He pulls a craggy oyster shell the size of my arm from a recently harvested cluster, a beatific glow across his face. Gulls circle above, evoking the sound of the sea; herons and cormorants silhouette in the distance, denizens of the bay. Tucked inside the barnacle-adorned shell is the essence of Yaquina Bay. It will taste like no other. “It’s what Mother Nature allows us to do,” says Xin.

Edible Portland, Winter 2009

Click here to read the article on the Edible Portland website http://edibleportland.com/sea-salt-kiss/.